You know when you start poking around data and then 175 hours later you realize you may have just gone a bit too far? That’s where I found myself recently when I began to dive into the world of long-haul narrowbody flying. We all know that the 757 is reaching the end of its stellar run and that the A321neo/LR/XLR is stepping up to take its place. But I wanted to really look into the data to better understand just how this was happening. The end result is a whole bunch of animated gifs that tell the story.

Note: If you get this via email and can’t see the gifs, make sure to click on the title in the email to read on crankyflier.com. It’s worth it.

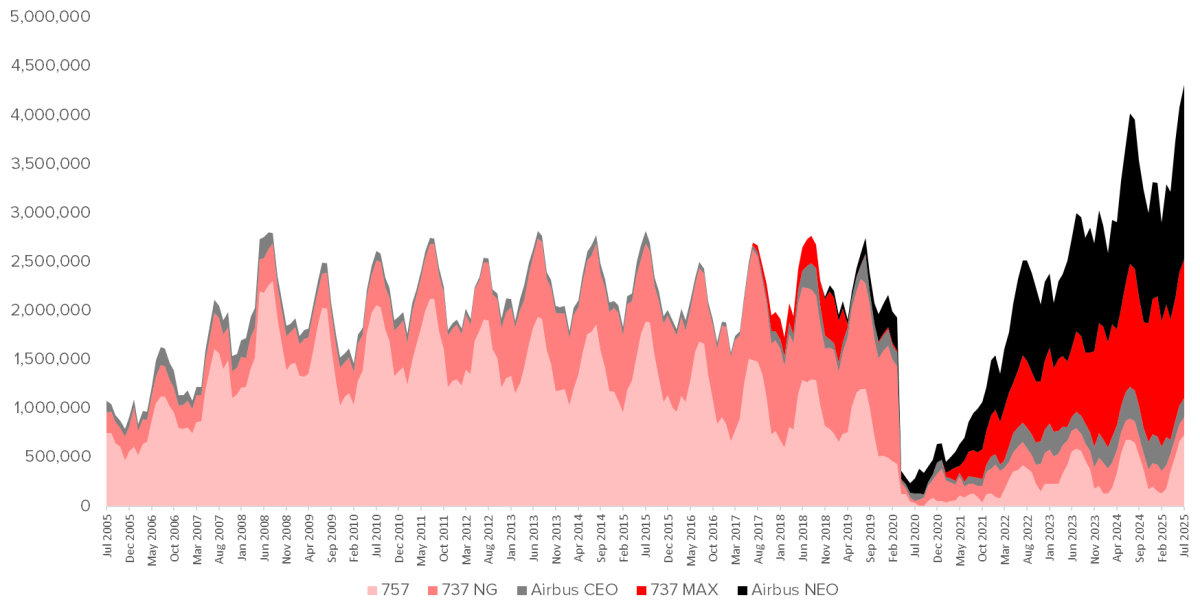

First, let’s start with a summary chart. I grouped narrowbodies into five groups:

757 – includes the 757-200 and 757-300 variants 737 NG – includes the 737-600/700/800/900 variants 737 MAX – includes the 737-8/9 MAX variants Airbus CEO – includes the A318/A319/A320/A321 current engine options Airbus NEO – includes the A320/A321 new engine optionsThen I pulled Cirium data for flights over 3,000 miles over time, going back to 2005. You can see definite trends here.

Monthly Narrowbody Block Minutes on Flights > 3,000 miles by Fleet

Data by Cirium

So, what do we see? The 757 was the absolute king of the road up until the pandemic. It wasn’t until the Great Recession when the use of the 757 peaked on long flights, but it remained very important until the pandemic when retirements hit that aging fleet hard.

Meanwhile, the 737 NG was surprisingly the second largest player in long-haul flying, but it only grew up until the pandemic. That was going to end when the MAX came online, but as we all know, that was grounded. So the rise of the MAX didn’t happen until after the pandemic.

The A321neo’s LR version didn’t come until much later with the XLR just having its first delivery to Iberia completed. Despite the later start, it has become the one to beat, by far showing up as the best 757 replacement. Boeing has gone from nearly 100 percent of this market to closer to half. And more will be ceded without a different aircraft for Boeing to offer airlines.

That’s the overview, but it’s the nuance that’s far more interesting. I put together a summer story by fleet that I’ve put into animated gifs. Let’s start with the 757.

Data by Cirium, Maps generated by the Great Circle Mapper – copyright © Karl L. Swartz.

I have put notations on each image as you can tell, but let’s talk through it a bit here.

In 2005, the 757 was going Transatlantic on short hops, and it was heading from Europe toward Southeast Asia. But in 2006, North American Airways decided to experiment with US – West Africa flying. And in 2007, Northwest pushed further inland in the US, operating Detroit flights to Europe. By 2008, First Choice Airways in the UK decided to do a ton of flying to the Caribbean and Latin America, it appears. I find it hard to believe that this was even possible, but it’s what the data shows. Take it or leave it, but either way, it didn’t last long.

In 2013, much of the 757 long-haul flying was starting to wane except for Transatlantic, and Icelandair really began to go longer-haul to the western US. In 2016, American had mostly left South America with those airplanes while in 2017 United began isolating its fleet further west in Europe, making for shorter flights and fewer fuel stops.

When the pandemic hit, the 757 fleet nearly ground to a halt. Icelandair was the only one really keeping its fleet going. But in 2022, United brought its 757s back into regular rotation. Other than those two, the long-haul 757 has largely become a tool of necessity. Russian airline Azur Air, for example, has pressed it into service as new aircraft become harder and harder to procure in that country.

Let’s contrast this with the 737 NG and A320ceo family. (I’m aware that the label is wrong in calling it a NEO, but it was going to be a real pain to fix. Sorry.)

Data by Cirium, Maps generated by the Great Circle Mapper – copyright © Karl L. Swartz.

If we go back to 2005, this was a very niche operation. Air France did some long-haul Airbus flying into Africa while Lufthansa contracted with Privatair to fly mostly 737s but also Airbuses in an all-business class configuration. The only non-niche operation was Copa which was just starting to flex its muscles from that Panama City hub.

In 2010, British Airways started its vaunted business class-only A318 service from London/City to New York, but it was 2011 when others began to test how far those 737s could fly. Turkish and Royal Air Maroc took their first swings that year and began growing SilkAir followed in 2015.

In 2017, Norwegian decided to test the waters by using 737-800s on those East Coast – Europe flights. In 2018, WOW Air in Iceland used A321s to try something deeper into the US. But that was about it except for La Compagnie using business class A321s and Air Transat pushing A321s into service until it had the neo aircraft to fly the full schedule.

The Airbuses were always minor players or placeholders while the 737s had some flying that was sustainable. But as soon as those MAXes came into play, they disappeared from long-haul pretty quickly.

And that leads us to the new generation. Let’s start with the MAX.

Data by Cirium, Maps generated by the Great Circle Mapper – copyright © Karl L. Swartz.

This is a much shorter image sequence since the MAX didn’t go long until it was delivered to Norwegian in 2017 to better handle those East Coast – Europe flights. In 2018, Lion Air, SilkAir, WestJet, United, and Smartwings all joined the party, but then it all stopped. The MAX was grounded in 2019 and went dormant.

Things started moving again in 2021 when Copa started using MAXs to replace the NGs. Turkish and Fiji did the same in 2022. Icelandair opted for the MAXs on shorter-hauls but it still needs the A321LR to truly replace the 757. Those are coming soon.

Then we saw Royal Air Maroc, Virgin Australia, and flyDubai join the party in 2023 with Alaska, China Southern, and Oman Air in 2024. We don’t know what 2025 holds for us yet, but TUIfly will be a part of the growth story.

The thing is, most of these aircraft are replacing 737 NGs. Sure, the MAX can do some shorter 757 stage lengths, but it is primarily just a more efficient way to fly what the NGs did and stretch a little bit further.

That is not the case for Airbus’s new generation which is almost if not entirely on the larger A321neo/LR/XLR.

Data by Cirium, Maps generated by the Great Circle Mapper – copyright © Karl L. Swartz.

In 2019, the neo began flying for Air Transat and Azores Airlines with shorter stages. Even S7 in Russia had high hopes that are largely dashed now thanks to geopolitics.

In 2020, American and TAP Air Portugal started going longer with the former connecting Anchorage while the latter did shorter Atlantic flying. SAS and Aer Lingus followed TAP in 2022, and JetBlue started its own Atlantic enterprise that year.

In 2023, we saw Jetstar launch some interesting flying from Australia while Gulf Air did it from Bahrain in 2024. Next year with the XLR finally taking flight, growth will zoom. As of now, we have Iberia and IndiGo having filed schedules with their first forays into long-haul narrowbody flying.

The reality is that the only real replacement for the 757 at the edge of its range and beyond is the A321XLR. That’s why both American and United have orders coming. When United takes delivery of its first in 2026, it will presumably go toward replacing the 757 first. Once that happens, the 757 will begin its inevitable final approach after a stellar career. A Boeing replacement remains just an elusive dream.