Over the past decade, there’s one truth that liberals have been loath to admit: Donald Trump is funny. This aspect of his appeal prompts far less commentary than his far-right positions, his venality or his mogul’s bravado. But when you watch him at a rally, you can see he’s playing for laughs: jabbing at his opponents, doing crowd work, even being self-deprecating, sort of.

Cicero could write a treatise on Mr. Trump’s use of irony, as he’s proved himself a master of humorous misdirection. Liberals tend to think that irony is a type of wit that is aligned with progressivism. But for nearly a decade now, if you went looking for comedy in American politics, Mr. Trump would have been your best bet for finding it.

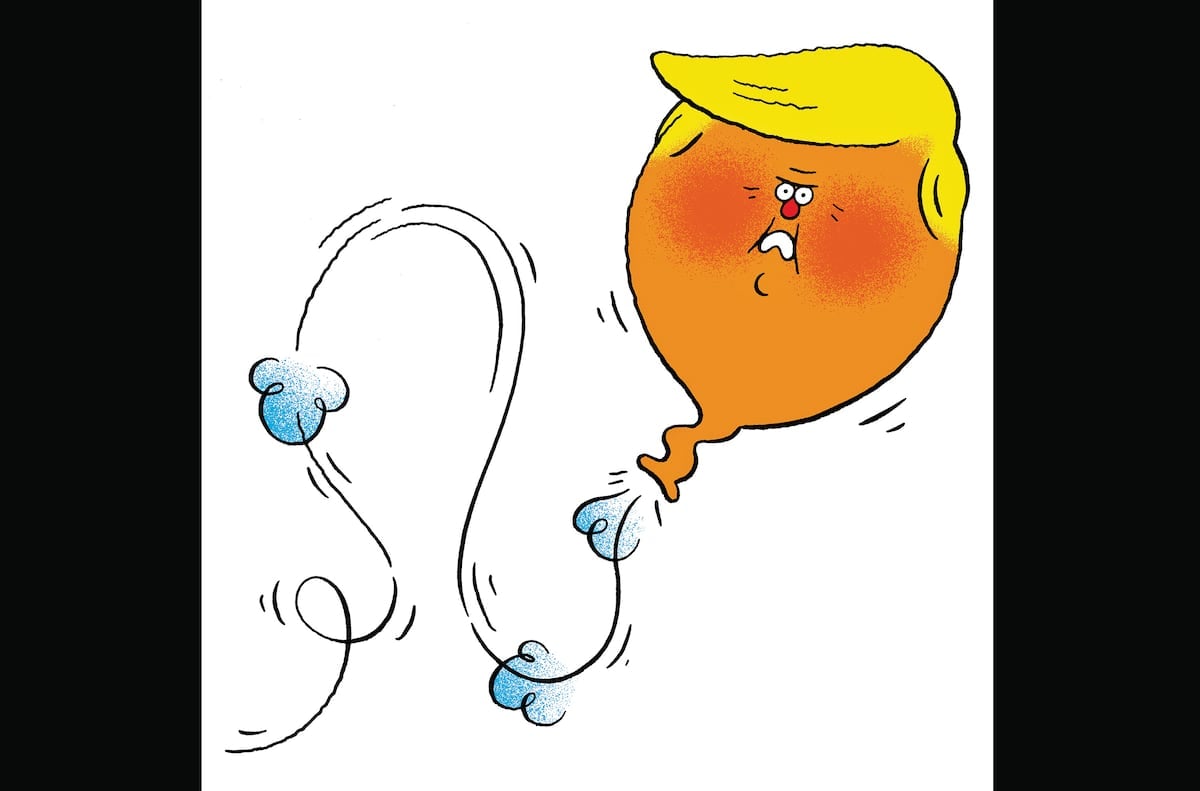

Now that magic is gone. Politics is about communication, and when Mr. Trump is on, his humor offers a clear outline of his worldview. These days, he looks lost. The fact that Mr. Trump is less sure-footed as a comedian may be a harbinger of a more significant uncertainty — an inability to land the punchlines because he can no longer identify the right setups.

Mr. Trump, a real-estate tycoon turned reality TV star, came to politics by way of humor. Whether it’s true or not that he decided to run in 2016 in response to President Barack Obama’s roast of him at the 2011 White House Correspondents’ Association dinner, there’s no doubt that Mr. Trump’s rise through the Republican ranks was partly thanks to his uncanny insult humor.

From the start, he evidenced an ability to pierce the veil of political politesse. “Low energy Jeb” Bush and “Little Marco” Rubio fell by the wayside as Mr. Trump marched toward the nomination. This was alpha male humor, Wall Street humor, but with Mr. Trump’s personal twist. He could quickly get under another politician’s skin while communicating real political points through jokes.

There’s something interesting about humor: We don’t get to choose what’s funny. We can be horrified when Mr. Trump says something like calling Elizabeth Warren “Pocahontas,” but the offensive jab also got at something real. Ms. Warren really did use a misleading claim to Native ancestry in her career and eventually apologized for it. Even through his racist dog whistles, you could usually hear Mr. Trump communicating a deeper, more viscerally effective point: Politicians are full of it.

When he was doing his best comedy work, Mr. Trump laced irony throughout his speeches. Irony is a technical term from the field of rhetoric, a technique that uses contradiction to convey meaning. Irony allowed Mr. Trump to nod to beliefs without ever having to explicitly state them, which in turn afforded him plausible deniability. When a reporter asked him about protests surrounding a Saudi-backed LIV Golf tournament at his Bedminster golf club, Mr. Trump said, “Nobody’s gotten to the bottom of 9/11, unfortunately” — practicing simple misdirection while also making 9/11 conspiracy theorists’ ears perk up. His brand of irony can land a punch, but just as often he uses it to breed politically useful confusion.

Recently, though, you get a sense that the light has gone out. Sure, he’s out there doing his Bob Hope thing, vamping on various topics, bringing out the hits — his weird digressions about Hannibal Lecter; his incoherent rant about sharks; and other favorites that lie squarely on the border between humor and possible cognitive decline — but the electric energy that made him an internet sensation is absent. Gone are the days of armies of trolls creating “God Emperor Trump” memes. Instead, he’s complaining about crowd sizes and attacking reporters for being rude. His abrasiveness no longer comes off as funny; it feels cranky and desperate. A recent post by Mr. Trump on Truth Social — his own social media platform — began, “I’m doing really well in the Presidential Race,” which sounds like whiny protest. It’s a far cry from such Trump Twitter classics as “Happy 4th of July to everyone, even the haters and losers!”

The Trump campaign has attacked Kamala Harris for laughing a lot, mocking her in memes and floating the nickname “Laffin’ Kamala” (easily the worst of Mr. Trump’s monikers for his opponents to date). But the gambit backfired badly, drawing attention to how Mr. Trump himself never seems to laugh, while Tim Walz, Ms. Harris’s running mate, touted Ms. Harris for “bringing back the joy.”

When Mr. Walz took a shot at JD Vance, his Republican counterpart, by obliquely referencing a viral joke about Mr. Vance’s relationship to (and with) couches, some pundits reacted with shock. But the tactic showed a Democratic ticket that’s willing to, well, make a real joke. The Harris campaign is also leaning into memes, embracing the idea that “Kamala is brat,” a slang term roughly meaning a little “messy” and popularized by the singer Charli XCX.

The Democrats have been many things over the last few decades, but funny has rarely been one of them. Now liberals are having fun and the MAGA movement that Trump commands is, for the moment, in a defensive, resentful crouch.

The advantage of wit is that it allows you to pivot, to change the subject, to be nimble and to dazzle your audience, all while giving it the impression that you’re in full control. Mr. Trump once had that power. But when reporters recently asked him whether he would ban the early-stage abortifacient mifepristone, his answer wasn’t witty — it was so garbled that it was hard to write headlines about. Irony can often be hard to distinguish from incomprehensibility, and Mr. Trump too often crosses that divide.

Losing a step doesn’t mean you’re finished, in comedy or in politics. Mr. Trump has returned to his favored comedy platform, Twitter (now X), so we’ll see if he can return to form. For now, pollsters may not capture exactly the role that humor is playing in our political preferences. But losing the humor advantage has made Mr. Trump seem directionless, listless and vulnerable. The energy that humor provides is now invigorating his opponents, who are looking to laugh him off the stage.

Leif Weatherby is an associate professor of German and the director of the Digital Theory Lab at New York University. This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

function onSignUp() { const token = grecaptcha.getResponse(); if (!token) { alert("Please verify the reCAPTCHA!"); } else { axios .post( "https://8c0ug47jei.execute-api.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/dev/newsletter/checkCaptcha", { token, env: "PROD", } ) .then(({ data: { message } }) => { console.log(message); if (message === "Human