This year Indigenous People’s Day marks 100 years since Congress enacted the Indian Citizenship Act, granting U.S. citizenship to Native Americans. Americans are usually shocked when they learn that those who preceded Europeans on this continent did not gain citizenship for more than a half century after the Fourteenth Amendment gave that status to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States.” But the reality is Indians have long had ambivalent feelings about U.S. citizenship. For centuries, Native peoples fought and maneuvered to maintain their sovereignty. Many feared citizenship would make them subject to state and local taxes, and that officials would use their power to take Native land and sell it to white ranchers, timber men, and farmers.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]In colonial America, the British Empire usually recognized indigenous sovereignty within their own territories. After the Revolution, the new American government continued that policy. For instance, the Constitution gave Congress sole power to regulate commerce “with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes” (Article I, Section 8), and also excluded “Indians not taxed” from the federal census. Indeed, in 1789, first Secretary of War Henry Knox told President George Washington that Indian tribes “ought to be considered as foreign nations, not as the subjects of any particular state.”

Read More: How Virginia Used Segregation Law to Erase Native Americans

In the 1820s, however, some states sought to impose their laws on Native nations within their boundaries. Mostly famously, Georgia moved to expel the Cherokee and force those who remained to become second-class citizens subject to an assortment of racial barriers, which the states had the power to establish and implement. The Cherokees, backed by northern supporters, went to the U.S. Supreme Court to challenge Georgia’s efforts as a violation of federal authority over Native relations. At first, in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), the court refused to help, noting that its jurisdiction did not specifically include Indian tribes, but one year later, in Worcester v. Georgia, the court ruled that Congress but not states had authority over Native nations.

Unfortunately, the two decisions put Indians into constitutional quicksand. Although the federal government continued to treat Indigenous groups as quasi-sovereign entities, that government also enthusiastically implemented genocidal removal policies from 1830 through the 1870s. Native groups forced to move west of the Mississippi and then to the Southern Plains, with little food or knowledge of their destination, often in winter, suffered high death rates from starvation and disease. Once there, they had to rebuild their communities and faced conflicts with already resident Native nations. Not surprisingly, many preferred to remain in their homelands. Some Ho-Chunks in Wisconsin, for example, became individual property owners under state law and trusted neighbors of white settlers. Groups of Cherokees in North Carolina and Choctaws in Mississippi gained state citizenship (and accepted racial handicaps) by explicitly spurning tribal sovereignty. Some also managed to avoid removal by hiding in the mountains or swamps.

The national push for Indian citizenship developed in the wake of the 1868 Fourteenth Amendment, which mandated birthright citizenship and barred states from limiting civil rights. One issue Congress debated was how this would affect the status of Native peoples. The ultimate compromise was to side-step the question by excluding “Indians not taxed,” following the Constitution’s rule for the national census, the longstanding principle that only states could levy taxes on individuals, and the belief that the authority to tax included other legal powers that would have violated federal authority and tribal autonomy.

In 1871, Congress moved towards ending Native sovereignty by declaring it would no longer authorize treaties, but instead would impose laws on Indians until they became full citizens and subject to the laws of the state where they lived, though all existing treaties would be respected. In 1887, with the end of the Indian Wars, Congress enacted the General Allotment (Dawes) Act, allotting reservations, keeping individual holdings in federal trust for 25 years, and extending U.S. citizenship along with all state or territorial laws to allottees. Political calculations led the bill’s authors to explicitly exempt the most nationally vocal Native nations, including the Senecas in New York and the “civilized” tribes in Indian Territory, soon to become Oklahoma.

Read More: The Ghost of Dred Scott Still Haunts Us

Many of the supposed protections built into the Dawes Act were tenuous at best. Every reservation allotment left huge portions of “surplus” land sold to white farmers and ranchers. In 1903, the Supreme Court in Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock ruled that Congress had the power to unilaterally ignore Indian treaties (all made before 1871), which opened the door to laws making it simpler for federal agents to sell allotments before the trust period ended despite the opposition of their owners.

These experiences fed Native fears that U.S. citizenship was intended to bludgeon rather than benefit tribes, and that the subsequent state and local property taxes would result in their lands being seized and sold to white men. That was why, after the Civil War, Indian communities in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island had (unsuccessfully) opposed the full citizenship proposed by those states. Elsewhere, Natives who retained allotments with federal trust status were apparently protected from that threat. Congress required territories seeking statehood to include measures in their constitutions prohibiting the taxation of trust lands. Still, the 1906 Burke Act allowed backdoor deals at the national level to end such restrictions. At one point, Congress considered allowing the taxation of allotments whose owners were “drunkards” or refused to surrender their children to boarding schools. While tribes could win protections—in 1912, for example, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress could not annul its 1898 agreement with Choctaws and Chickasaws for a 21-year trust period—taxation remained a potent threat.

By the early 1900s, many Natives viewed U.S. citizenship as part of their route to participate as equals in America’s economy, politics, and culture. The first modern Native pan-tribal organization, the Society of American Indians, formed in 1911 by young boarding school graduates, put citizenship at the top of its agenda. This was followed by wider Progressive reforms (including allotments and individual enterprise) that they saw as necessary improvements for individual Indians and their communities.

When it was finally enacted in 1924, the Indian Citizenship Act was hardly a revolution: about two-thirds of Natives were already citizens due to narrower federal or state laws. The Act explicitly protected “the right of any Indian to tribal or other property,” and some states continued to restrict Native voting until the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Some Native groups, such as the Onondaga in the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederation, explicitly rejected citizenship as an illicit reduction of their sovereignty and began to issue passports to their people. In 1934, during the New Deal, federal policy would take a U-turn and foster rather than eliminate Native nations and their governments.

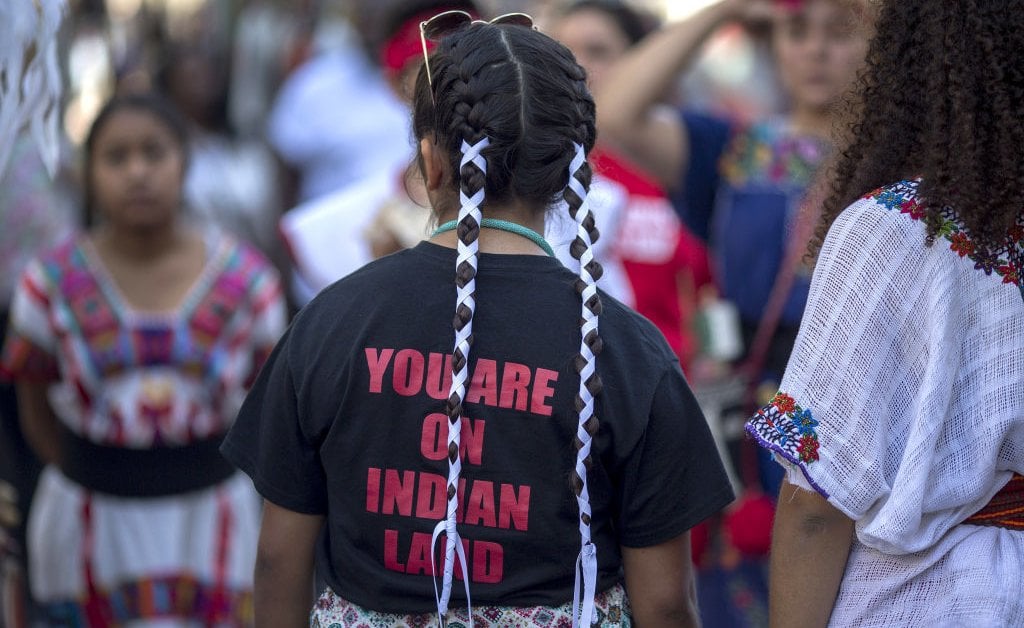

Today an Indigenous American, if a registered member of a federally recognized tribe, is a citizen of that tribe, the U.S., and their state. Indians serve in the U.S. military at five times the national average, and veterans receive special honors at community gatherings. Elected tribal governments exercise local police powers and (like their state counterparts) administer many federal programs. But tribes continue to be buffeted by state challenges and federal actions, and Native people continue to defend their remaining sovereignty and unique trilevel citizenship.

Daniel Mandell is Emeritus Professor of History at Truman State University, Missouri. He is the author of various works on New England Native American history including Tribe, Race, History: Native Americans in Southern New England, 1780-1880; and Behind the Frontier: Indians in Eighteenth-Century Eastern Massachusetts.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.